Gentle Decline 2/3: Dissonance & Digressions

In which a reader's question is answered, and some media are linked

Hello. This issue starts out on cognitive dissonance, based on a question from Eva, and then wanders off into how people see and understand change, and then chases down a few useful links and bits of news, and really I should start doing a table of contents or something.

Gentle Decline is an occasional newsletter about climate crisis, and - more to the point - how to cope with it. Drew, who needs to eat as well as rant, has a Patreon at https://www.patreon.com/drewshiel - specially requested by readers of this newsletter and Commonplace. You can see details that didn't make it into the newsletters, for a start, and Patreon backers have already had a look at the upcoming Gentle Decline T-shirts and other goods. Sign up today! Alternately, go for the coin-in-the-busker’s-hat at Ko-fi.

NEW: $1 Patreon Tier, for those that just want the occasional Patron-only posts and such.

Eva said: “I'd love to hear you talk more about the weird dissonance of looking at these facts while still functioning in a society that really doesn't seem to be taking any of them in. I know very few people who seem to be cognizant of the fact that we are already living through changes and those changes will continue and increase in severity, or they may be cognizant but it's not impacting on their plans in life in any meaningful way. Perhaps it's a sense of helplessness?”

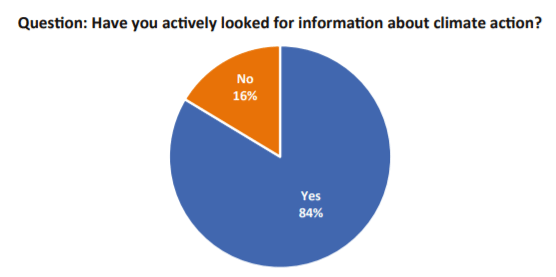

This is a complicated area (echoes of “that’s a great question” as the speaker tries to think). First, people are definitely concerned about climate issues, and becoming more so. In Ireland, The EPA has a good report from 2018 on how people view such issues, and it contains - among many other interesting data, this pie chart:

Now, this is being drawn from focus groups, who were to some degree self-selecting for people who wanted to talk about the topic, and also has the usual caveats of direct interview wherein people will say what they think the interviewer wants to hear. And:

It is important to note that the findings are not generalisable to citizens in Ireland. They provide examples of recurring themes that circulate and exist within a group of concerned and well-educated citizens. […] Moreover, the findings do not include uninterested, disengaged or denialist perspectives on tackling climate change.

But 84% of those people had either gone looking for information, or thought that they should have, so we can take that as a reasonable indicator that at least some people know stuff is happening. There’s also a lot of material in that report about how climate information is communicated, how people receive it, what sources they trust, and so on. Friends & family, as ever in Ireland, account for a very high proportion of trusted information.

I haven’t gone chasing down statistics in other countries in any detail, but the general impression I have is that in the Anglophone world and in Europe, pretty much everyone is on board with the idea that climate issues are real. The USA is the one main exception to this, where membership or support of the Republican party correlates massively with climate denial, and that’s about half the population. I don’t think we’re dealing with rationality there; that’s tribal signaling of some kind (and I’ve written elsewhere on how I think that comes from sports “news” reporting).

So, I think people are cognizant of the fact that an issue exists, which is, more or less, step one.

So, the next natural thing to do is ask “what can I do?”. And there are answers! So many answers! You can fly less, take public transport, recycle more, reduce food miles, buy goods with less packaging, reduce water use, install solar panels, buy energy from green companies, grow wildlife gardens, and a hundred other things!

And this step is where it falls apart, because there are two separate issues following this. One, all those things above (except, perhaps, flying less and wildlife gardens) cost more money than their environmentally damaging counterparts. And by the time you’ve taken into account the slowness and expense of surface travel when necessary, and buying specific plants for wildlife, rather than just mowing the lawn, you’re probably looking at equal or greater expense in both of those areas too. And all of them chew up time and reduce your available choices, sometimes quite starkly.

Two, even if you do all those things, nothing changes. All the bad numbers keep going up, all the good numbers keep going down, and there is absolutely no sign that you have made one bit of difference. But, the imaginary voice in my head says, that’s because it takes everybody doing it to make a difference. And that is not entirely untrue; if everyone did these things, we would probably see some impact on the numbers.

The problem here lies with the emphasis on individual action. I’ve written about this before too; the efforts needed to make a difference need to come from companies, not individuals, and until there is a cost for not undertaking those efforts, nothing much will change. The “social cost” of public disapproval isn’t much of an impact (although it is some impact, and makes some difference) and mostly results in companies doing stuff to clean up their images, not their actions. What would make a difference is legislation. If there is a tax on corporate flights, a tax break for employees using public transport, fines for not recycling, extra taxes on packaging and water use, tax breaks and (real) grants for solar panels and buying energy from green companies, and fines for lawns, all of these things will suddenly change.

And then there are the things companies do that individuals don’t, like heating large, often mostly empty buildings, having uncontrolled emissions from factories and plants, causing oil spills, and so forth. Those could be penalised a lot more. But because corporate interests lobby government, fund political parties and campaigns, and generally deploy money to prevent this kind of legislation - because it’s cheaper for them than complying would be - it doesn’t happen.

So, that’s why we’re not seeing change despite people’s own efforts, where they’re happening. Many people are discouraged by this, but they go on trying, at least at the token level. They don’t know what else they can do to make a difference. And the kind of changes that I’m advocating in this newsletter are either too big and disruptive (move inland), too time- and effort-consuming (grow food), or kinda vague (be generous). Also, it bears saying that my advice here is intended to mitigate the effects on individuals first, and work at broader and societal levels second, and to reduce the actual climate change only third; that’s within the context of corporate entities not changing their practices. I do not believe that that is the overall best course of action, but it’s the niche I’m working in, and one where I can make a difference.

So now we have “people are cognizant of issues, but the things they do have no effect”, which we can imagine is (or can experience directly as being) pretty disheartening. So the next thing that most folk are going to do is take refuge in denial. “Well, maybe it won’t be that bad,” “Sure, what’s a few more storms? We’ve always had storms,”, “Cork has flooded all my life, it’s not really any different”, and “I looked at the flood maps, and sure two metres is nothing much”.

(It will be that bad, more and bigger storms can be devastating, especially once they cross the threshold of ‘worst storm’, Cork’s floods are getting worse and have been getting worse for two hundred years, and two metres is actually huge in terms of the damage it will do, because so much of our civilisation sits right on coastlines. Sorry, I can’t let this stuff pass, even when I’m rhetorically saying it myself.)

But because very little of the efforts that are being made - where efforts are being made - are visible, denial seems reasonable, somehow. “If it was going to be bad, the government would do something about it.” That one, there, the trust in authority - I honestly think that’s one of the main problems. It might even have been justified, once upon a time, although I suspect that the era of attention-paying newspaper-reading people who voted on the basis of policy proposals and actual outcomes is as fictional as any other halcyon-days-of-yore vision.

I have a whole ‘nother rant about about how Western education systems, the glorification of STEM subjects over humanities, and the portrayal of government agencies in fiction and media leads to people thinking that the authorities can be trusted.

But suffice it to say: with a very few exceptions, even the best people in legislative branches of government have a horizon that stretches as far as the next election and no further. Many more of them have a horizon measured only in dollars. Climate crisis can still be kicked down the road a few years, since “nothing has happened yet”, and so it will be. The actual civil service and some - not all - of the government agencies may be trying to get stuff done, but funding comes from the top, and funding drives everything.

Anyway: the idea that the authorities would be “doing something” if it was “really that bad” is the main driver in most people’s (approximate) comfort with climate inaction.

I have two more points before I wander off into different digressions, and I can’t find ways to wedge them into the reasoning above, so you’ll have to deal with the written form of “and another thing!”.

First: people suffer from Shifting Baseline Syndrome. This is the fancy name given to the inherent belief most people that the state of affairs when they start paying attention to a situation is “normal”, and everything that happens thereafter is “change”. When in reality, change has been under way for some time. This means that “ah sure, we’re always had storms” sounds reasonable for anyone in Ireland under about sixty years of age - while in reality, we’ve had more and bigger storms since the 1980s, and the trend is upward in both frequency and in force. The number of birds and animals seen in the countryside has been decreasing for centuries, but we only really notice the small decrease in our own lifetimes, assuming we’re paying attention at all. I was outside in fields a lot in 2020, and I do not recall seeing a single rabbit. I saw more foxes, but foxes are scavengers.

Second: there is a correlation between age and concern with climate crisis. Younger people (under 25, say) are far more likely to take the issue seriously. This is in part because they’ve had the education about it; their school science and geography has included it as basic fact, where that of most people reading this probably didn’t. But it’s also in part - and probably more - because they’re the ones who’re going to experience it. Some optimistic reports say “sea level rise of 2m by 2100”, and us old folks (I am 43; grade my level of cynicism based on this) go “well, I won’t see that”. But to someone who’s in their teens now, it’s very likely that they will see that, and they’ll definitely see 1.5m. I feel that a key aspect of putting information out there is to make sure that those people can see ways forward, rather than being stuck with a broken world given to them by their grandparents.

Alright, those digressions:

An excellent primer on the hard science of Carbon Dioxide Removal. I don’t want to declare that it’s essential reading, but it certainly goes a long way toward equipping you with an understanding of what needs to happen and how it can happen. Which will allow you to see how it’s mostly not happening.

In a bit of clarity which unfortunately is not even slightly surprising, Ireland has apparently been absolutely dire in compliance with EU environmental directives. “The Department of Environment was asked for a response but it commented only on the breaches of the Waste Directive referred to by Judge Collins, saying while historically Ireland may have been slow to implement policy, the country was now on course to meet all obligations.” Uh-hunh.

Wired has a short article on the Civilian Conservation Corps, a Great Depression-era program of employment and infrastructural maintenance. Apparently President Biden has proposed a “Civilian Climate Corps”, which would be a very similar program. Seeing as this is pretty close to the concept of Guaranteed Employment, of which I am a big fan, and comes with resources to throw at the climate crisis, I’d be very happy with it. And with the US engaging in something like this, it’d become a lot easier to persuade Ireland to do so; there’s still a strong strain of belief in the goodness of the Land of Opportunity among our government castes.

The UK suffers from flooding nearly as much as Ireland does (or more, sometimes), and its flood defences are not in good order. There’s the observation as well that “[t]he figures show that 8% of those managed by third parties are in poor or very poor condition, compared to 4% of those overseen by the Environment Agency. In the picturesque district of Hart, in Hampshire, all of its vital flood defences are managed by third parties and nearly half are in a state of ruin.” 8% and 4% sound like low numbers, but in flood management, any defence failing means that the system has let water through, and once that happens, huge amounts of flooding can happen. It’s somewhat akin to saying that only 4% of a balloon’s surface is on the verge of bursting. But once more, vital or emergency services fail more in private hands (although the 4% under the Environment Agency are obviously an issue as well).

The following images tweeted by JC are becoming all too normal because of this:

(JC has provided me with more pictures and data, so I’ll dig into that a bit more in a future issue.)

And finally a piece of more positive news: a study on how mostly grassroots efforts in a poor area of Mexico City are helping deal with the effects of climate change; mostly flooding from changed weather patterns. That’s the kind of thing I’d like to see here, although it’s likely not to happen until after people have encountered flooding or other issues.

This issue brought to you by rain and more rain, bits of freelance work, and more assisted research from Cee. I've given up on trying to say what the next issue will be in advance, but I'm taking requests and questions, like Eva’s which provided much of the content of this one.

Gentle Decline is on Twitter as @gentledecline, which I’m using more these days.

[Support this newsletter (and Commonplace, its food-related sibling) and allow me to keep on eating while I hammer on the keyboard and interrogate government sources. Patreon is here, and for those thinking more of the one-time coin in the hat, Ko-fi is available.]