Gentle Decline 2/28: History & Habitation

Talking about history, and climate history, and what we might learn.

Hello. It’s been a while. Many of you will know that I don’t deal well with heat, and this summer has been warm for quite a bit. Add to that some illness in the early summer, and some just plain busy-ness since, and things get away. This issue has been in process for a while; I’m going to look at previous climate changes and how people handled those. When, that is, there were people around to handle them.

[Gentle Decline is an occasional newsletter about climate crisis, and - more to the point - how to cope with it. All issues are free! You can support the newsletter via Patreon (where there’s sometimes further discussion about particular points), Ko-fi, or by buying some of the seriously classy merchandise, including the new Plant More Trees t-shirt.]

Positive Things

A new climate law in the US could have global benefits. There’s a way to generate electricity from nothing but humid air.

Ice Ages

The main changes in climate this planet has seen have been from either cataclysmic events - the Cretaceous-Paleogene meteorite impact being the prime example - or from shifts between the Earth’s two steady states. The cataclysmic events include meteorites, volcanic eruptions, possibly some other tectonic plate movements, so forth. As far as we can make out, they result in short-term changes from stuff thrown into the atmosphere, which reduce the level of sunlight reaching the surface, and make for a few years of winter - maybe even as long as a century. Obviously, that’s bad for everything that lives on the surface, but it’s not completely lethal - some light still gets through, there are probably even sunny days sometimes, but the overall energy level is diminished. Usually, this effect fades out.

The flips between steady states are probably, in a natural state, slower. The planet has in the long term two very different steady states, one called “Snowball Earth”, where there is permanent ice over a good part of the surface, and glaciers that reach or almost reach the equator. There’s still some room for life in that equatorial zone, but not much. And the reflective effect of the ice keeps the planet from actually warming up, so it can stay in this state for a very long time. There’s an argument that this is the “natural” state of the planet; what it would be like if there were no life here.

But there is life, and there are also tectonic effects, which can release a lot of heat from the planet’s interior. Life - plants, specifically - produce carbon dioxide, and decaying life produces methane. Both of these are greenhouse gases, which will warm the planet up even in a very cold state. And once the planet gets some momentum in that heating, there are feedback loops, and a pretty fast process - in geological terms - toward the other steady state, an ice-free planet. Once that state is achieved, the planet absorbs more heat, rather than reflecting it, and plant life thrives, so there’s more carbon dioxide and eventually methane. It takes a winterising effect like a volcano or meteorite to provide a chance for this to flip back.

In the most technical of terms, we live in the gap between these states. The planet is neither covered in ice nor ice-free, and at a crude level, this is what has allowed for humans to develop things like agriculture and thereby civilisation. There have been slight wobbles in this state within the lifetime of the human species - much of Eurasia and North America were covered in ice up to about 11,700 years ago. The last time the planet was ice-free, though, was at least 30 million years ago. Seeing as modern humans have only been around for about 200 thousand years, that’s well before our time.

Here in Ireland, the last ice cover melted in that 11-12 thousand years ago range (the end of the “Younger Dryas” period). So our landscape is only that old, effectively, and sea levels have been rising since as the ice melts. Sea levels at the end of the Younger Dryas seem to have been about 60m below our current (slightly out of date) marker for them. Doggerland - an area in what’s now the North Sea - was probably above water until about 7000 years ago. This is within the period of human habitation there; various evidence of tools and other markers of people have been dredged up by fishing vessels since the 1930s or so.

So we know that people coped with rising sea-levels in at least that era. We don’t have any idea how they did so, though; writing wouldn’t happen for another two thousand years or so in Sumer, so there’s no record beyond the archaeological.

Medieval and Renaissance Climate Blips

There were a few more climate oddities during actual recorded history. I want to look at two of these: the Medieval Warm Period and the Little Ice Age.

The Medieval Warm Period happened between about 950 and 1250CE. It wasn’t a single event globally; there are different start and end points in different regions. It included such effects as better crop yields and increased flooding (meltwater from snowpacks and glaciers), and allowed the settlement of Iceland and Greenland. It was, in short, a period when the warming effects were noticeable, and had effects on culture, agriculture, and trade that are absolutely visible in the historical record.

That period was followed almost immediately by the Little Ice Age, from 1250 to about 1850CE. It’s notable that our idea of “what winter should be like” in Western Europe was pretty much set during this period, when there more frequent and deeper cold snaps, when snow could be expected pretty much every year, and when rivers and lakes fairly routinely froze over. The whole of the Baltic froze over twice in the early 1300s. The Thames froze over often enough between 1600 and 1800 that there were Frost Fairs on its surface. The Victorians in particular produced a lot of imagery and writing with these assumptions - which, to be fair, were normal and true for them - and we’ve never really updated our concepts, despite 170 years of mostly damp chilly and rain-filled winters since.

Is what we’re facing different?

It’s not entirely easy to put numbers on either of the medieval climatic periods. But it’s broadly true to say that temperatures during the Medieval Warm Period were about 0.5C to 1C higher on average, with much of that in winter, so that you might more accurately call it the Medieval Not As Cold Period. And then during the Little Ice Age, temperatures were perhaps 1.5C below the long-term average.

We are already about 1.1C above the pre-Industrial average, and we’re certain to hit 1.8C in the next few years. Most projections agree that a rise of 2.7C by 2050 is pretty likely. So if you look at what happened during the two historical eras, we can expect a lot of effects in the next twenty years, which will probably not ease off anytime soon after that. It is different. It’s unprecedented in human history, and you’ve got to go back to about 5 million years ago to find similar temperatures.

The Medieval Warm Period is also called the Medieval Climate Optimum. It allowed for a lot of things to happen that wouldn’t otherwise - viticulture in northern Europe, including England and possibly even Ireland, the aforementioned settlement of Iceland and Greenland, and better crops in lots of places. In North America, the same period - more or less - included a number of severe droughts, and may have contributed to the abandonment of Cahokia.

We’re already looking at a greater increase in temperature, and we’re seeing consequences of this in terms of drought, forest fire, and extreme weather. There probably will be some changes that are beneficial to people in the short or medium term - and there definitely will be in the longer term - but these will come at a cost. Viticulture gain in northern Europe will be matched by places in the south that can no longer grow grapes at all, for instance.

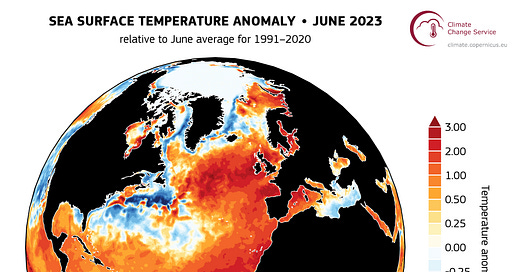

The Little Ice Age can serve as a kind of preview of what will happen if the Gulf Stream shuts down. I wrote about that recently in Issue 2/24 and in more detail back in Issue 1/23, and there are measurements this year of a very anomalous high temperature in the Northern Atlantic, which is not helpful in terms of increasing glacier and icecap melt.

To be honest, we’re better equipped culturally to handle that than an increase in local temperature - as I said above, our idea of what winter is like was set by the Victorians, and that has been continued with American TV and its depictions of the New England winter.

One of the things to note here is that the settlement of Greenland eventually failed. It wasn’t a complete collapse (thanks, Jared Diamond, you hack), but it was definitely a withdrawal as the Little Ice Age cut in. Iceland hung on to people, but it’s never been a populous place. Some of the short-term benefits of climate change will be subsumed into climate chaos - you can’t grow grapes easily in a place that has frequent hailstorms, for instance. Ireland has already had more thunderstorms this summer than in years before. Here’s a germane quote from Met Éireann research meteorologist Dr. Pádraig Flattery:

“As climate change continues, we can expect further records to be broken and more frequent and extreme weather events. A warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture (about 7% for every 1°C of warming) and warmer waters, in turn, provide more energy for storms and can contribute to extreme rainfall events.”

It’s interesting to see a figure for moisture attached to the warming trend - the 2.7C increase expected by 2050 would translate to about 18.9% more moisture, which given that this is already frequently a pretty soggy island, would be a lot. And, of course, more storms. Further, because atmospheric movements can cover a good part of the globe in a few days, even if we get the cooling effect of the Gulf Stream failing, we might also get more storms anyway - drenching thunderstorms in summer, and snowstorms in autumn and winter.

Usefully, we’ve already got a pretty strong pandemic-driven cultural movement under way towards remote work. That will stand us in good stead in a period of more extreme weather. And Ireland’s roads - particularly our major motorways - are in genuinely good condition to hold together against poor conditions, which is more than can be said for the UK, US, or Canada.

Closing

Alright, that’s enough doom-mongering for now. I’m going to attempt to do a little more digging on how European communities dealt with - and took advantage of - the Medieval Warm Period, although I don’t expect that to be fast research. The next issue will, ideally, look at climate fiction in the last couple of years, and what we’re seeing there that might help with preparations for the next few decades.

[Support this newsletter (and Commonplace, its (more) food-related sibling) on Patreon or Ko-fi. Merchandise is also available. Major research contributions in this and all issues by Cee.]